Bridge Generation Personality of the Month: Joe Talaugon, 93

Joe Talaugon

His first day of school was awkward. When his teacher asked for his name, Joe couldn’t answer. He didn’t know his given name! He was always called “Sonny” — often the name for the oldest boy in Filipino families. Finally, he came up with “Joe” — as his father was called by his friends. Actually, friends called his father “Cadjo” — short for Arcadio — which when spoken with an accent, he heard as “Joe.”

One evening when Joe was in his teens he overheard his parents arguing. It was about his illegitimate birth. His father had always treated him as a son. In many ways, he was treated better than his siblings. But his father apparently had mixed feelings about Joe’s paternity. Joe began remembering — whenever his father was asked by friends if Joe was truly his son, he would say “yes” while at other times he would say “no.” Joe became ambivalent about his father. As time went on, however, the pain of rejection lessened. His parents remained together for more than 20 years until 1952, when his mother left after another argument with his father. In 1969, Joe tragically lost his father in a fire at the family farmhouse.

The pain of being rejected by his father may have lessened, but it never went away. When he was in high school, Joe turned to alcohol to escape. He began drinking alcohol in excess after celebrating a football game. Despite being the high school’s star halfback at 150 pounds and in the glory days of an athlete, this marked the beginning of Joe’s alcohol addiction for the next 14 years. Today, Joe finds it almost unthinkable that he “actually lived those times of awful shame as a pitiful, disgraceful example of a human being.”

Joe is now 93 and has not had a drink for almost 40 years, proud that he was able to quit “cold turkey.” Time helped. His acquired spirituality, self-discipline, and skills in blue-collar and farm jobs also helped. However, he credits the love and support of his petite Pinay wife, the former Margie Cabatuan, with being of most help. Joe met Margie in high school. They went steady until August 25, 1950 when they eloped in Yuma, Arizona. Joe was drafted into the U.S. Army shortly thereafter. Following basic training, he was assigned to Camp Gordon in Georgia where cheap, home-brewed “white lightning” was easily obtained from bootleggers.

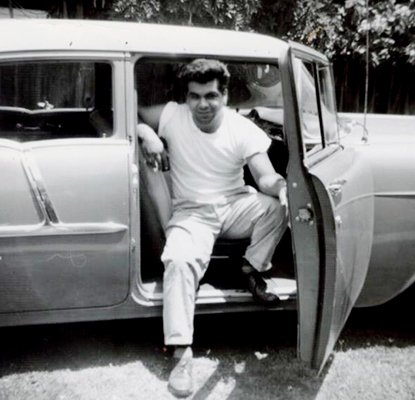

Joe and wife Margie

Despite his drinking, Joe was honorably discharged in the summer of 1953 and began working as a lettuce dry packer alongside more experienced manongs in Guadalupe. Taught by an elderly manong, he became one of the fastest packers in the work crew. Dry packing lettuce, like most farm labor, is long and hard but the pay is much better. Its drawback? Joe had to travel as a migratory worker that went to where weather was favorable for growing lettuce.

But a migratory life was not long for Joe. In 1955 he took advantage of the GI Bill and enrolled at a Los Angeles trade school, graduating in 1957 with a certificate in sheet metal work. Life for Joe and his family significantly improved with his increased income and from owning a restaurant in Guadalupe — Margie and Joe’s Restaurant — bequeathed by Margie’s Uncle Matas. By 1965, however, construction jobs declined. Moreover, they now had more children. In 1967 Joe and Margie moved to Northern California where Joe was employed in building trades in Stockton and Sonoma County for 17 years and in a San Francisco printing business for eight years.

Joe in his younger days

Perhaps as economically significant as Joe’s NorCal employment was Joe and Margie’s immersion in community activism in Sonoma County. In Guadalupe, Joe and Margie saw how decades of isolation and discrimination impacted the manongs, leaving them with little dignity and resources. The Filipino community in Sonoma Country was developing programs for Filipino elderly; Joe and Margie eagerly joined the effort.

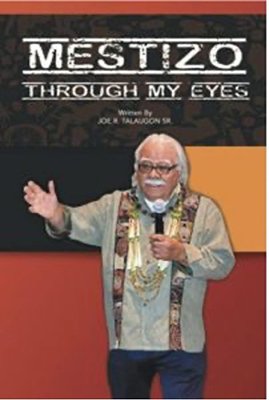

The year 2020 was a notable one for Joe. It was the year his autobiography Mestizo Through My Eyes was published, a book he began writing 47 years earlier.

Northern California was also spiritually significant for Joe. In August 1988, he learned that a Wintu Tribe Spiritual Woman named Flora Jones was scheduled to lead a three-day celebration at the base of Mount Shasta. This was an opportunity to learn about his Native American side. At the celebration’s final event, he was selected by the Spiritual Woman to sit on the Sacred Circle with five shamans in a special ceremony. The six participants took turns smoking a ceremonial pipe, blowing the smoke towards Mount Shasta while Flora chanted in her native tongue before praying for each of the participants. Joe still recalls feeling “a connection with the Great Spirit” and becoming “filled with pride and inner strength.”

In 1989, Joe and Margie determined it was time for them to return to Guadalupe. They purchased a home on the outskirts of nearby Santa Maria and immediately became involved in the community, including the Central Coast Chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society. In 1995 Joe was among featured speakers as FAHNS dedicated a plaque commemorating the first landing of a Filipino in America in Morro Bay in 1587.

A member of the Chumash tribe, Joe received a significant windfall in 2003: gaming income from the new Chumash Casino Resort. With the increase in income, he purchased three buildings in Guadalupe. One became a home for Joe and Margie. The other two buildings housed Margie’s dream: The Guadalupe Cultural Arts and Education Center. Sadly, she passed away before the center was completed. Today, Joe manages the cultural center of four galleries which features monthly exhibits and art shows.

The year 2020 was a notable one for Joe. It was the year his autobiography Mestizo Through My Eyes was published, a book he began writing 47 years earlier. The book is not only a story of his life, it also is a story of the struggles of the Manong Generation’s in an often unfriendly America. (The book may be purchased online on mestizothroughmyeyes.net.)

Mestizo Through My Eyes

Reflecting upon his life, Joe considers his seven children to be his greatest joy. Coming in a close second was working and living with the Manong Generation whose experiences have largely been written by authors who never lived or worked with them. (Acknowledgement: Joe Talaugon May 7, 2024 interview; Mestizo Through My Eyes; Wikipedia.)

Peter Jamero was born in Oakdale, California in 1930 and raised on a Filipino farm worker camp in Livingston , California. Recipient of a master’s of social work degree from UCLA, he is a trailblazer having achieved many “Filipino American Firsts” in his professional career. He is the author of Growing Up Brown: Memoirs of a Filipino American and Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation. Retired, he lives in Atwater, California.

More articles from Peter Jamero

No comments