First Filipino Fire Survivor Report Stresses Financial Needs

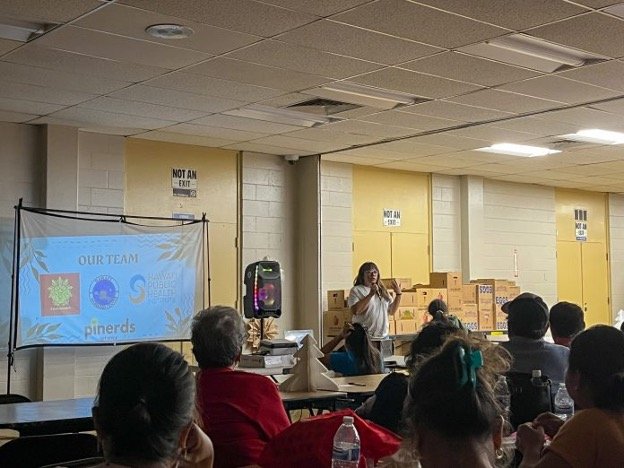

Nadine Ortega presents the first report on Lahaina Filipino fire survivor needs. (Photo By Yiming Fu)

After last August’s Lahaina fires that burned down the historic downtown, these large family units have been separated into different fire survivor housing assignments. Their familiar routines are different now. Krizhna Bayudan, the Lahaina organizer for Hawaii Workers Center, said families are not sure they can get back together after the rebuild.

“When it came time to separate into these smaller units, people lost that sense of community and their lives were tipped upside down,” Bayudan said.

The first report on the needs of Filipino fire survivors comes 16 months after the fire and calls for intergenerational housing to restore family support networks. Tagnawa and Hawaii Workers Center released the report December 15 at a Paskua event with Zumba dance performances, free box lunches and food pantry goods for attendees.

Tagnawa is an organization that empowers Filipino voices in the wildfire recovery and Hawaii Workers Center provides resources and training for low wage workers. Bayudan, who is a Filipina fire survivor herself, organized the event and conducted interviews for the report.

An Unheard Voice

Lahaina’s Filipino community is large but often underrepresented. They make up about 40% of the West Maui town and are often called the backbone of Lahaina because many Filipinos work service industry jobs in the hotels. Most Filipinos also work multiple jobs, meaning they don’t have time for civic engagement at official county events. There is little to no Filipino representation in county government nor in legacy media.

“There has been only a limited effort to go to the Filipino community and ask them for their input. To engage them and ask them and give them the tools to rebuild Lahaina,” Nadine Ortega said.

Ortega is the founding director of Tagnawa and presented the fire survivor report. She is from Oahu and after the fire didn’t know if she should encroach on the Maui community during a sensitive time. But a few days after, she heard countless stories of Filipino family and friends on Maui not knowing where to turn for resources, not being able to understand the technical jargon and being yelled at by culturally insensitive disaster recovery workers.

A couple weeks later, Ortega conducted a needs assessment event at the Royal Lahaina with other community volunteers and organizers. She posted one flier online a couple days before. The day of, the event was supposed to start at 11 a.m. but people already began lining up two hours beforehand.

“We were like oh my god why is it so packed here? They were waiting for us.”

This report is the first comprehensive study on the needs of Filipino fire survivors, conducted by Filipino fire survivors through phone calls, questionnaires and culturally sensitive conversations in people’s homes. Participants chose to respond in English, Tagalog and Ilocano, with more than half of them picking a non-English option.

Daily Challenges

Participants discussed challenges not knowing where they will live long term, struggling to put food on the table because of rising costs of living and high rents, and one in three study participants discussed mental health challenges, like being traumatized by siren sounds and always having a bag packed in case of a fire.

The community asked for clarity and assurance about their future in Lahaina, wanting to plan for years ahead instead of a year-to-year basis. They also asked for more inclusive approaches to affordable housing eligbility and a common sentiment shared was “awan marunongmi” or we don’t have money we can save.

The report also emphasized a need for affordable, long-term housing options that can accommodate multigenerational living —68% of Filipino families lived in these multigenerational households pre-fire where they could support each other.

Most of the times, the houses were owned by one family member, with the other relatives all paying below-market-rate rents. Now family members are not sure if they’ll be included in their family rebuilds, since people do not know if they have enough money to build back the same number of bedrooms.

Bayudan said when families were split up, that often meant losing your babysitter, your transportation, or the cook of the family. Having this housing arrangement could address housing, mental health, food insecurity needs and more.

“Everything is just up in the air,” Bayudan said.

“When it came time to separate into these smaller units, people lost that sense of community and their lives were tipped upside down,” Bayudan said.

Rooted at Home

The first Filipino laborers arrived in Hawaii in 1906 to work on plantations where they would dig irrigation ditches, plant, harvest and process sugarcane. As Lahaina transitioned from sugar and pineapple plantations to a tourism-based economy in the mid 1900’s, many Filipinos were ushered into service jobs in hotels, restaurants and resorts. After a few years, many Filipino immigrants would bring family to Maui as well.

Ortega hopes the rebuild of Lahaina will move away from focusing on tourists and focus on ways that Filipinos can support and work for each other.

“I think we need to kind of diversify our economy, figure out a way to have like an economic system in Hawaii that’s good to the land, good to Native Hawaiians and good to Filipinos — that’s going to allow us to to live and take care of each other,” Ortega said.

Despite sixteen months of uncertainty, Bayudan stressed that Lahaina’s Filipino community is committed to staying and rebuilding.

“They always say this is all I’ve ever known,” Bayudan said. “This is the community we’ve poured our hard work into. This is where all of our family and friends are. They love Lahaina and want to stay and rebuild here.”

First posted in AsAm News: https://ift.tt/ds2948w

No comments