Visayan Pop Music’s Rise and Stall

Stereotypical Filipino serenade (art by Markytour777)

But where did it all start, and why do Vispop artists continue to embrace the genre, despite its lack of support, funding, and recognition? Let’s go through the evolution of Visayan music, and the emergence of Vispop, across different time periods, but for lack of information on songs in other Visayan languages, this timeline will mostly focus on Cebuano.

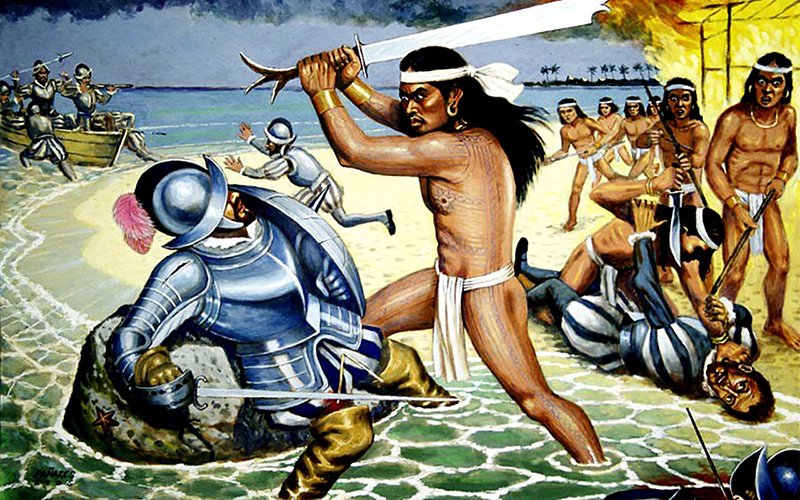

Spanish Flop

For half a century, citizens and agents of the Spanish Empire kept trying to establish a colonial outpost on the Visayan island of Mactan. We all know what happened to Magellan in 1521. In 1565, Legazpi came to the neighboring island of Cebu, renewing the Empire’s attempts to occupy the region. The Spaniards built plenty of Spanish-style architecture on the island and started a settlement, with Legazpi becoming a governor. The Cebuanos gave them a hard time, running to the hills, hiding whenever the foreigners tried to force them into providing services. As Visayans were stubborn, defiant, and uncooperative, the Spaniard finally gave up in 1570, Legazpi sent an expedition to the northern island of Luzon, and founded a new capital, the city of Manila, the following year.

The death of Magellan (art by Manuel Panares)

As a result, Spanish scholars observed that Visayan culture in the 17th century had remained relatively untouched, although the province of Bohol had embraced Catholicism and Hispanicization by this time. Chirino’s and Alcina’s texts have one thing in common despite the almost 70-year gap between their chronicles: both say that the Visayans loved to sing and play musical instruments until they literally passed out. Alcina even claims that only illness or sleep could stop the Visayans from singing. That’s also true for modern Visayans (I’m addicted to karaoke, for example).

Tool of Colonialism

Eventually, the Spaniards figured out how to make the Visayans their loyal subjects.

One of Chirino’s chronicles observes that in pre-Hispanic Visayan societies, divorce was normal, common even. It talks about a woman from Carigara. The unbaptized native Visayan did not want to give up her freedoms as a woman, such as the right to abandon a husband who displeased her, or enjoy casual sex. The woman later did return to church and get baptized, after Spanish Jesuits convinced her that she’d burn forever in Hell if she continued to practice indigenous spirituality and culture. The Spaniards also used the Visayans’ love of music to promote Catholicism, and in turn, the religion promoted Hispanicization. The Visayans syncretized native culture with Spanish culture. The balitao, a Visayan musical style with likely pre-Hispanic origins is a good example.

The exact origins of balitao can’t be traced, but there’s an ancient term for it, ayayi. (The exact meaning of ayayi has been lost in time.) A balitao often involves a woman interrogating her suitor, a far cry from the stereotypical “traditional Filipino serenade,” in which a woman passively observes as a man does all the talking.

Pre-Hispanic Visayans used bamboo flutes and guitars fashioned from coconut shells for the balitao. However, after Spanish colonialism took hold, the harp replaced these instruments. Fun fact: Visayan harps are more visually diverse than Ilocano harps because the former were usually fashioned by the harp players themselves, who personalized their instruments.

In the Spanish era, balitao lyrics became increasingly Catholic, talking about the Creation, the Nativity, and other topics from the Bible. Some Spanish words also seeped into the Visayan languages. (Interestingly, though, the more modern balitao songs t I’ve heard so far all deal with romance and marriage. I’m curious about what those Spanish-era Visayan songs sounded like.)

In 1904, Visayans, mostly from Iloilo, were exhibited in one of the USA’s infamous “human zoos” at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. An American newspaper from June 9, 1904 describes the Visayans as “representing the higher type of lower class civilization.” Visayans sang and danced to songs in English, like The Star-Spangled Banner. This assured white Americans that yes, these “wild” people could be tamed. Music was no longer a vehicle of self-expression for the Visayans; instead, it became performative and passive, an object for the consumption and comfort of imperialists.

Visayan girls with the USA flag, an exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (photo Jessie Tarbox Beals, courtesy of Missouri History Museum)

Soft Power

In 1946, the USA granted the Philippines independence. But later, the Americans took control of Filipinos again via a soft power. This time, many Filipinos fell under the spell of American pop music.

From the 1920s to the ‘70s, Cebuano-language music began booming. Even Manila-based companies like Villar Records sought Cebuano talents up until the ‘70s. Cebuano cinema also began to flourish. In the ‘80s the popularity of MTV and American pop songs among Cebuanos put an end to the golden age of Cebuano-language media.

In the ‘90s, Cebuano music acts still existed, like the bands Local Ground and Mango Jam that wrote songs in English. Bands of the 2000s released songs in Cebuano. In fact, Missing Filemon’s iconic hit song Englisera seemed to satirize Cebuanos who preferred English. But this movement was pretty short-lived. In the early 2010s, new hope for Cebuano music emerged when musicians Jude Gitamondoc, Insoy Niñal, and Cattski Espina founded the Visayan Pop (Vispop) Songwriting Campaign.

Despite its name and the founders’ acknowledgment of other Visayan languages, the contest focused on songs in Cebuano. Vispop often uses a mix of Cebuano, English, and sometimes Tagalog. The songs are in the Westernized pop style. Some purists might claim that it’s not authentic; for me, though, Vispop is just an evolution of Cebuano music.

As much as Filipinos love to romanticize about cultures staying “pure,” Vispop is beautiful; it has definitely helped many Gen Z Filipinos (like me) to appreciate and embrace my language. Despite its use of English and Western musical styles, it’s a great vehicle for Visayan self-expression.

Vispop steadily rose in popularity throughout the 2010s, the Filipino American Karencitta’s smash success probably being one of the game-changers paving the way for a boom in Vispop songs in the current decade. In 2020, Puhon by beloved singer-songwriter TJ Monterde, written in fairly “deep” Cebuano, quickly surpassed the one million-view mark on YouTube, indicating a popular appetite for Vispop.

In February 2021, the multilingual boy band ALAMAT debuted, with songs in Visayan languages like Cebuano, Waray, and Hiligaynon. Their first single, Kbye, entered Billboard USA’s “Next Big Sound” chart. Maris Racal (Asa Naman) and Felip from SB19 (Palayo) pushed Vispop to national, even international consciousness. BINI’s B HU U R from their October album Born to Win even included a few lines in lesser-represented Visayan languages, like Akeanon.

The genre continued to flourish. In 2022, Shoti’s LDR went viral; Wilbert Ross dropped the super sweet Langga, a love song with a Cebuano title and a verse in the language. Morissette Amon, who is globally recognized as “Asia’s Phoenix,” released her first Vispop song, Undangon Ta Ni. But in October, Gitamondoc warned Cebuanos about Manila organizers planning to stage festivals during Sinulog week, drawing attention away from already-underappreciated Cebuano artists.

Cebuana_American singer Karencitta with fellow Cebuana singer, Morisette Amon

In January 2023, Careless Music’s Wavy Baby festival in Cebu removed almost all of their Cebuano acts from the line-up. Vincent Eco from the Vispop band The Sundown remarked (in a mix of Cebuano and English), “Yet again, [brands] will hold concerts in Cebu, but Cebu bands were made disposable.” Vispop icons such as Kurt Fick and Jacky Chang, whose songs attracted millions of views and streams just a year or two ago, no longer pulled big numbers. Following the success of their Tagalog single Maharani (which bestselling Filipino American author Melissa de la Cruz even mentions in her 2024 romance novel The Five Stages of Courting Dalisay Ramos), ALAMAT started to release multilingual songs less and less.

The years 2023 and 2024 were rough for Vispop. At this point, the industry seems to believe that Cebuano-language music is no longer worth the gamble. The regional music scene also suffered without a new Vispop smash hit. But glimmers of hope have emerged here and there. For example, Felip released another Cebuano single, Kanako, a pop-rock love letter to his fans.

Dom Guyot also released Free in 2024, an effervescent ode to the queer Bisaya experience. That same year, Juan Karlos Labajo released a fully Cebuano song, Kasing Kasing, with fellow Gen Z singer Kyle Echarri. Labajo explained that he and Echarri were planning to write the song in Tagalog, but decided to write it in Cebuano instead because why not? It’s their mother tongue, after all, and the language deserves representation.

Morissette Amon is also embracing Vispop and her Cebuano identity more than ever. In a January 2025 interview with Rappler, Amon revealed that people in the industry told her that she would never achieve fame if she didn’t speak and sing in Tagalog. Although singing in Tagalog and English (and even other foreign languages) is what she’s known for, it’s amazing that Amon chooses to stand by Vispop and pursue self-expression in Cebuano, even if it may not be as remunerative as her mainstream ventures.

Despite the departure of ALAMAT’s Ilonggo member Valfer, and the band mostly putting out Tagalog singles in the past few years, the arrival of Don’t Play in February was a breath of fresh air. Their Davaoeño member, Alas, wrote the song in a mix of Cebuano, English, and Tagalog. It was a one-man effort all throughout, with Alas working on the production and songwriting independently. Don’t Play has a lyric visualizer that follows him on a date with a faceless girl. It’s sweet, although far simpler than the lavish, cinematic music videos that his group is usually known for. His years-long effort to develop the song and the passion that Magiliws (ALAMAT fans) have shown for it have been so heart-warming. Even if Vispop, and Visayan media as a whole, lack the funding or spectacle of imainstream, it’s still beautiful and worth your time.

Perhaps most unexpectedly, BINI’s meteoric rise to stardom has led to many Blooms (BINI fans) taking an interest in Cebuano. Although the group’s one and only song with any Visayan in it was from three years ago, fans are generally aware that Cebuano is the first language of BINI members Aiah and Colet. A while ago, a Google Doc teaching basic Cebuano was going viral among Blooms on social media. Many Blooms have pledged to learn the language so they can understand their idols better.

Colet of BINI performing the Vispop song "Puhon" with TJ Monterde (photo by MyTV Cebu)

In February, Colet also showed off her signature high notes in a surprise Puhon duet with the man himself at TJ Monterde’s concert. The screen behind them displayed the Cebuano lyrics, paired with Tagalog subtitles, to the tens of thousands of concertgoers at the Araneta Coliseum (“the Big Dome”).

Music in other Visayan languages still struggles. In 2023, a duo called JAXX released a pop EP in Hiligaynon, but their effort only earned them 27 monthly listeners on Spotify (as of writing). Eliza Maturan got her well-deserved fame lately, but her Surigaonon track Ijo Ton Bayay has enjoyed far less recognition than her Tagalog songs. The most recent Waray pop song I could find was Payong by Fordy (2023); the most recent Akeanon one was Ikaw Eang ag Ako (also 2023, and still has under 800 views until now). But one man, Raffy Buenavides, is still actively making Hiligaynon songs.

Despite its use of English and Western musical styles, it’s a great vehicle for Visayan self-expression.

It’s clear that the road to recognition for Vispop is going to be very steep. Even Cebuano pop, which definitely has the best infrastructure in the Visayan music industry, is still struggling with a lack of support and funding. Yet, Visayans keep making music.

So, Dom Guyot is right: Visayan pop is here to stay, even if Visayan artists don’t get the VIP treatment. It’s here to stay even if Visayan songs don’t get budgets or investments from big networks. It’s here to stay even if songs in Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Akeanon, etc. fail to reach thousands of listeners. Why? Because Visayans love music, and our languages are integral to our lives.

Julienne Loreto (they/them) is a non-binary university student with roots in Bohol and Leyte. They are also a writer whose articles have been published in the prestigious music magazine The Line of Best Fit, as well as the Asian-American magazine JoySauce; their fiction stories have also been selected for publication by 8Letters and sold at the Manila International Book Fair.

Some sources for further reading:

● https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/1506389

● https://www.ijams-bbp.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/1-IJAMS-NOVEMBER-21-30.pdf

● http://jacklegpreacher.com/filipinoharp/ch3/ch3.htm

● https://muse.jhu.edu/article/737320

● https://www.rappler.com/entertainment/music/interview-morissette-album/

● https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0967828X.2023.2229488

No comments