Prewar Family at Maja Lane

The staircase at Maja Lane (Photo by Tara Illenberger)

March 2021. A year into the Covid-19 pandemic. I stumbled upon a photograph of the remains of the old concrete stairs of an abandoned house. It was from a Facebook posting of Tara Illenberger, a young filmmaker. She posted “Remains of the Day” photos of abandoned homes in the City of Iloilo. I wrote and promised Tara, that one day I will tell the story of these stairs and the family that had inhabited the house on Maja Lane.

Last December my oldest sister, Maja Teresa Concepcion-Guerrero passed away. She was 91. Fortunately, I had succeeded in persuading her to write about her recollections as she was growing up. She left a trove of memories.

Maja wanted to be a writer, but our Tatay (father), had other plans. After graduating at the top of her class in high school, “Tatay took me to Manila to study pre-Law at UP (University of the Philippines), although I would rather have studied journalism,” according to Maja.

Tatay’s brother, however, convinced him to have Maja pursue a CPA degree, after which she could then study Law. The University of the East (UE) had built a strong reputation, consistently topping CPA Bar examinations. She ended up enrolling there, graduating at the top of her class. Maja was to study law next, but fate intervened again. UE offered to underwrite the cost of her pursuing an MBA degree from the famed Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Chicago, where she broke the glass ceiling. She was the first female to have been accepted at Kellogg.

I am sharing excerpts from Maja’s chronicle of the war years 1941 to 1945, partly to honor her childhood dream of becoming a writer. Maja wrote, “I have always loved writing, but I was frustrated in my quest for journalism.”- Rogie Concepcion

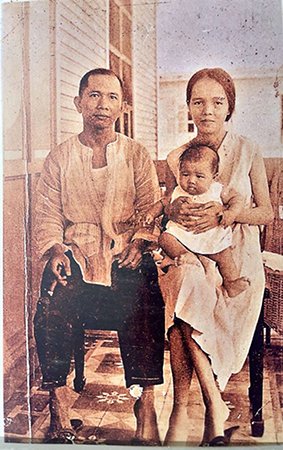

Prewar Family at Maja Lane

My recollection of my father’s early years is sketchy as he was reluctant to talk about himself. What is vivid to me was his support and encouragement of any intellectual pursuit we made. Education to him was paramount; money can be lost but what you learn stays with you throughout your life.Tomas was born in 1896, the youngest of six children of Proceso Concepcion and Teresa Poblador of Pototan. Why Proceso and his brother, Venancio, migrated from Alaminos, Pangasinan, ending up in Negros, no one still living knows. Proceso was the Juez de Paz (Justice of the Peace) of Silay, while Venancio, became a Philippine revolutionary general during the Philippine-American war, and later became the first president of the Philippine National Bank.

While Venancio was at war, Proceso was left to take care of both families. Because of the family situation, Tatay had to send himself to school as a working student. The Americans recognizing his talent, sent him to the United States as a pensionado. He ended up at Columbia University and had Carlos P. Romulo, who eventually became the President of the United Nations General Assembly, as a roommate. Tatay was fond of recounting how he helped with the math assignments of Romulo while Romulo returned the favor by helping him with his English assignments. After his return, Tatay went back to Iloilo to practice law, opting to go back to where he felt he was needed more.

My mother, Julia Jalandoni, in her senior year in the College of Pharmacy at the Centro Escolar University in Manila was a beauty queen, having been voted Miss Pharmacy of Centro Escolar. She happened to be the eldest daughter of one of Tatay’s rich clients. My Lolo Colas (grandfather) was extremely frugal, or kuripot. He saw an opportunity to get free legal services forever and offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to his lawyer who could not believe his good fortune. My mother’s opinion was not solicited, but being the dutiful daughter, she obeyed her father. Despite its arranged beginnings, the marriage turned out to be a good one; they were devoted to each other until they died.

Julia Jerez Jalandoni, Nanay

December 18, 1941

We were getting ready to go to school, my sister Alma and I, when we heard ominous foreign sounds in the air. Japanese planes were dropping bombs on the Iloilo Trade School, behind our house. I was about 8 years old and my sister 6 years old. The first Japanese bomb fell near our kitchen. We heard a loud boom followed by the shrill frightened voice of my mother screaming to bring my sister and me down to our cement staircase while she ran down, cradling our baby brother. I do not remember seeing our father. Where was he? Maybe, trying to save his valuables and papers. All of us crouched and huddled in a small cubbyhole under the cement staircase, not knowing what was happening, while we listened to the successive explosions of bombs. We later learned that the men were watching the dogfights between American and Japanese planes.

The high school boys at the trade school had been practicing marching with their wooden guns. They were Philippine Military Trainees or PMTs (which students translated as “pusil mo tapi” (your gun is made of wood). Others teased and called them “pisot mo tiko (uncircumcised).” But they were no match to the invading Japanese army.

The cadence of their marching ditty went like this:

Ari kami karon. Soldado ni Quezon.

Sapsap balingon, sapsap balingon

Ang amon ikaon.

(Here we are, soldiers of Quezon

cheap dried fish, cheap dried fish

Is what we eat)

Outside our house, there was pandemonium. There was panic in the streets. People were running helter-skelter and screaming. My godmother, who lived next door, ran into the street and boarded the first bus which was full of screaming women. She left her children behind, not intentionally but from fright. People do crazy things when frightened. Two days later she returned sheepishly to her home where she had left her husband and children behind.

One day, we had just come home from school, I saw two of our household help rolling up some gauze on the dining table. Curious, I approached them and asked, “What is that?” My mother saw me, and she hurriedly shooed me away. I went to play with our paper cut-out dolls from the Sunday papers with my sister. We had very nice dolls like the Dionne quintuplets, all five of them seated on a swing, but they were locked up in a glass cabinet. Nice toys were made for looking not for playing. That was the adage of parents then.

Our mother seemed anxious, and we seldom saw our father. Our household did not seem to be the same. My mother no longer smiled putting away things, while my father was busy with his papers. Our orphaned cousin, Nang Te, told us later that Tatay had buried money in the garden. But all of these were over our heads and my sister and I kept on playing with our paper dolls.

Bakwit: Evacuation to Safety

A group of men from my grandfather’s farm outside the city arrived. Our Lolo had already brought his family out to his farm at Banga-Bante in the town of Zarraga and sent for Nanay and our family. The next day we were on our way to Lolo’s farm. Lolo had a bamboo and nipa house. There was construction going on as the bamboo and nipa house was enlarged. It was our first experience to live in a nipa house. It was built on stilts with bamboo floors that allowed the food to fall to the ground in between the bamboo slats. The chicken below waited for the morsels of food. These were organic chickens as we call them today. There was a large community room where we ate and slept. My uncles and other men slept in a separate room downstairs. Lolo and my father were the only men who slept with us.

What fascinated me was the bamboo staircase. At dusk the bamboo stairs were hauled up and the hole on the floor was closed with another door. In the early morning, the stairs were dropped down.

We all slept on the floor in the main room. Our family, mother, father, my sister, brother and I shared one mosquito net. My cousin and two aunts slept in another, and Lolo and Lola, under one mosquito net. We had no mattresses, just the plain bamboo floor covered with large mats or banig. I do not remember having a hard time sleeping on the bamboo floor. In the morning, the household help rolled up the mats and the mosquito nets and pillows and kept them in a small room, Japanese style. The main room was always neat and clean. There was nothing in it except for a few bamboo chairs, the dining table, and stools.

At 4 a.m. every morning, Lolo started singing hymns of praise to the Blessed Virgin aloud. This went on for about an hour. He sang hymns praising her. It was very impressive because he never went to mass. When he finished, we all went back to sleep.

Cumpayan 1942: The bandit Juanito Buyong

One of the places we also evacuated to was Cumpayan in Zarraga in the hacienda of Don Modi Ledesma, the father-in-law of Tay Pepe. Tay Pepe was Tatay’s oldest brother. It was always a tug of war between Lolo Colas and Tay Pepe. Lolo Colas always wanted to have his favorite eldest daughter close to him while Tay Pepe always wanted to have his youngest brother, Tatay, stay with him.

Life in Cumpayan was idyllic at first. Fighting was in the cities, not in the farms and haciendas. There was chaos in the city, no government, as the Japanese had only just come in and had not yet organized the city administration.

One evening, a jar of Ponds facial cream fell on my head. My mother bent down to kiss me and apologized. It was around midnight, and it seemed that the household was awake, feverishly packing. For what reason, I had no idea.

The Japanese were in the city. There was no police presence anywhere else. The guerilla movement was not yet organized. Bandits were rampant and roamed the province without restraint. One of the most celebrated was Juanito Buyong. (buyong for bandit). Tales of his daring feats as far as Iloilo City under the very noses of Japanese sentries were spread orally, or by radio puwak; the bravery and effrontery of his daredevil deeds grew by each telling.

In Cumpayan, there was fear among the wealthy refugee families. Aside from the families of the brothers (Tay Pepe and Tatay), there was the family of Tio Modi and other families from Jaro. So, a neighborhood ronda (patrol) was organized and armed. The men took turns, together with men they conscripted from the tenants of Don Modi. They were not aware that Juanito’s mother lived in the hacienda and that Juanito himself grew up there. None of the locals said anything. Someone said later that Juanito himself took part in the ronda to guard against the bandits when he visited his mother.

One afternoon, Nay Rosalina (Tay Pepe’s wife) and Nanay were chatting in the yard. Children were playing games around them. Suddenly we heard the thunder of horses’ hooves. I hid behind a bamboo post which offered no protection, but I was near Nanay. Suddenly a man with a rifle and on a horse burst into view followed by other armed horsemen. My heart started thudding in my chest, but Nanay and Nay Rosalina fearlessly faced the armed intruders. The gang leader asked if they had seen a woman pass by. When they said no, he wheeled around and thundered off on his horse. There was great consternation all around and everyone started to ask what was happening.

I pieced together the story. It seems that this Juanito Buyong and his men went to lloilo City and snatched the mistress of an important man. She was a former candidate for Miss Philippines and very beautiful. He brought her to Cumpayan to his mother’s house. At one point, she asked to go to a non-existent bathroom, and she was brought to a field to relieve herself. Somehow, she managed to mesmerize her guard and they both escaped. That brought down Juanito’s wrath, who then proceeded to reveal his true identity. But when he turned to chase the runaway beauty queen, he left a parting message that he would be back the next day.

With this ominous threat, there was consternation and fear among the refugee families, so the men started to organize the trek back to Iloilo. Better to face the Japanese than the lawless Juanito Buyong who was also rumored to be very cruel. Not a Robin Hood was he.

That is what brought the Pond’s cream jar on my head, the hurried packing. By early morning before dawn, all the covered wagons drawn by carabaos were on the road to the city. We traveled under cover of the darkness. The next day, Juanito Buyong was back with his followers armed to the teeth. He was angry that we had all fled. He turned and crossed the river to the Gustilo hacienda nearby and massacred the entire family living there, except for one son who managed to escape. He especially tortured the mother who, the locals say, was cruel to one of the helpers related to him.

Back to the City: Return to Maja Lane

After I was born, the subdivision that Lolo owned in Lapaz became known as Maja Lane. My father built a house to welcome his new bride. It was crowned by a stone staircase with tiles from Spain. That staircase still stands, although the original house burned down during the war.

I remember that house as if it were only a few years ago. Some memories stay with you for a long time. My father planted a pine tree in front of the house which was encircled by a strip of cement. Around the pine tree were flowers and plants. It grew to a height which was almost near the eaves of the house.

It was a beautiful sight. Attached to the low circular cement wall was a pond where my father had raised goldfish. My cousin said that Tatay finally got rid of his pond because the cats always beat him to his goldfish.

When you went up the cement staircase with the Spanish tiles, your step on the porch which was also beautifully tiled. Next to the living room was the dining room and at the end of the dining room was where my piano was.

The goldfish pond with Tatay looking at Rogie. At the bottom of the staircase is a small compartment where the family took shelter when Japanese planes bombed the trade school behind the house.

Newborn Maja, with Tatay and Nanay in the tiled balcony of the staircase.

Then there was another room with a staircase going down to the ground floor. I do not remember what this was used for. Probably a second dining room where the household help would eat. I remember the kitchen porch on the second floor. It overlooked the grounds of the Iloilo Trade School.

By that time, American and Filipino soldiers had ended their Death March from Bataan, and the Japanese were entrenched in the cities. The Japanese army had bivouacked in the Trade School and there was a very large kawa or tub with a fire underneath in the yard which was directly in the line of sight from our porch.

Every afternoon, the Japanese soldiers would line up, the officers in front. One by one, they would step into the hot or warm kawa and then out, but they were all stark naked. My two aunts, cousin, and my sister and I would watch them every afternoon. Until my father found out.

The next day, our view was completely blocked by a bamboo screen. At the time, there was no television and looking at those soldiers was our only form of entertainment. They were dipping their bodies into the hot water. I was ashamed and never bothered to look down at their legs. My two aunts and cousin kept giggling with a steady stream of comments until Tatay put up the bamboo screen.

Japanese Ronda

Japanese officers occupied the empty houses on Maja Lane. We were the only Filipino family living there. The officers were mostly educated doctors, scientists, and businessmen. The Japanese doctor cured our simple ailments and gave us medicine. Every evening after dinner, dressed in their kimonos and wearing Japanese slippers, they would come to our house. My aunts and cousin taught them to dance, and I played the piano. Fortunately, I could play by ear or oido. Many years later, one of the officers visited Tatay on Maja Lane and asked for me, the “little girl who could play the piano well.”

One early morning, we woke up to the sound of Japanese boots running up the stone staircase and the sight of Japanese soldiers peering through our windows. I heard Tatay and Nanay talking excitedly to a Japanese officer who wanted to bring Tatay with them. Nanay was in tears and frightened because when the Japanese picked up someone the chances of that person returning home were very slim. Downstairs, we were all cowering in fear under the cement stairs because we were scared of the Japanese soldiers who wanted to come in. Suddenly, we saw some high-ranking Japanese officers, our neighbors, who usually spent their evenings at home, arrive. They barked at the soldiers who bowed and withdrew. After scolding the soldiers, these officers apologized to Tatay and left.

I asked one of them how my sister and I could go to school. We had tests and I was worried that we would miss those. He wrote a note in Japanese characters and gave the paper to me. We walked to school with the note. The only elementary school open was the public school near the plaza. Around the plaza was the church, the elementary school, the municipio, and the homes of the rich.

When Alma and I reached the main street, we saw at every lamp post a Japanese soldier with drawn bayonet. Except for the soldiers the street was empty of people. Not even a dog or a cat was on the road except the soldiers and two little girls. The first soldier shouted at us. I handed him my precious paper. He handed it back to me and motioned us to go ahead. We did this several times until we were in view of the plaza. There, a fierce Japanese officer, obviously in charge of the entire operation, saw us and shouted at the soldiers. He was mad that the soldiers had allowed two little girls to go through their gauntlet. Then two soldiers turned us around and pointed to where we had come from. Go back!!

We turned around and went back home but not before we saw that the plaza was full of men at attention. Some were dressed in pajamas, some were shirtless, most had not combed their hair and were either in slippers or barefoot. Obviously, like us, they were awakened from their sleep and dragged to the plaza. No one had time to escape. The Japanese soldiers had encircled our town and dragged out all males from their beds. Even my three uncles, Nanay’s brothers, were there we learned later. Lolo and Lola had also moved back from the farm since the Japanese did not seem to bother the inhabitants, as long as you bowed from the waist to them. We did a lot of bowing.

Unbeknownst to us, there was a dreaded ronda going on. In a ronda, all the male population of a town were brought to the plaza with their hands tied behind their backs. Then one or two Filipinos whose heads were covered with paper bags scrutinized the faces but did not speak. When they pointed to a person, that person was dragged out by a soldier, never to be seen again. He was suspected of being a guerilla. The other men were released and allowed to go home.

After the war, I was curious as to why Lola always sent a sack of rice to their neighbor every year without fail. When I asked, my aunt told me that Lola was grateful that this neighbor did not point to my uncle. It seems that he was suspected as being one of the Japanese collaborators or whatever they called those traitors.

Liberation Day

We were in the town of Dumangas when the Americans landed in the island of Panay. Clandestine radio stations gave exciting accounts of the battle at Leyte, one of the greatest naval battles of all time. One afternoon, I noticed I was alone on the second floor of the house we were staying. Perhaps everyone went away to escape the increased attacks of the guerilleros on the Japanese, or to attend the wedding of my aunt to an officer in the guerilla movement.

It was a little after noontime. The highway was deserted, which was rather strange. Then, the stillness of the afternoon was broken by shouts of teenagers and young men running down the highway screaming at the top of their voices. “Nag landing na ang mga Americano (The Americans have landed)!” People poured out of their homes. Everyone, I suspect, was glued to secret radios, including my own family. This is why I was alone on the second floor.

Not long after, the air was filled with deep rumblings. Soon, the first of the khaki-colored American trucks hove into view followed by many other vehicles including tanks. The soldiers were throwing candy, cigarettes, cookies to the people. But they did not stop because Iloilo City was still occupied by Japanese troops, and they were on their way there to oust them.

When peace was restored, we went back to our house on Maja Lane. It was a shock! Whereas we had a house before we left, the only visible object now on the street was our cement staircase. The devastation was widespread. There were no more trees or plants. Everything had burned down, whether by the retreating Japanese or the advancing Americans. Three streets away, there was a lone, empty, tiny wooden house standing. How it escaped the fires was inexplicable. Rather than sleep in the open on the ashes of the burned houses, we camped in that house. I don’t know how Nanay and Tatay managed to feed us as there were no markets and no stores left standing.

Tatay built a house of nipa, corrugated iron, and scrap material using the cement staircase as the main entrance. On the top right side of the cement staircase, there was a brass placard which read:

Tomas Concepcion

Abogado

Maja with Alma in the temporary replacement house made with nipa leaves after the old house was destroyed in the war.

Tatay’s brass nameplate that hung at the top of the staircase

Maja Teresa Concepcion-Guerrero (1933 – 2024) was a pianist, educator, writer, and entrepreneur. The youngest full professor at University of the East, who helped establish UP Cebu’s Graduate School, she authored two books. She was CFO and Vice President of Franklin Templeton Resources (third largest mutual fund) bank in San Francisco. With husband, Mike Guerrero, she owned and operated the 50-bus fleet of San Francisco Minibus. Maja was a well-loved mom and wife.

No comments