Imprisonment and Torture at Fort Santiago in World War II

Mr. and Mrs. Enrique Fernandez circa 1960s (Photo courtesy of Manny Fernandez)

Manny joined the US Navy in adult life; his younger brother, the US Air Force, but did not stay long. His dad, Enrique, lived to tell about his 38-day ordeal in Fort Santiago from August 8 to September 24, 1944 and wrote a testimony.

Before he died some years ago, Manny spent some days talking to this writer about his own experiences. And tangentially, his dad’s.

“The first time I encountered them at the school yard, I saw this Japanese soldier standing with the iconic kepi-style cap. And I thought, wow, they were small. I was more curious than scared.

“The second time I encountered them was in Nueva Ecija where my dad built a little nipa hut. We were at breakfast when we heard gunfire. We knew it was Japanese because their rifle had a distinct sound: tik-boom, tik-boom, tik-boom (probably because the Arisaka rifle was bolt-action, not automatic.)”

They found out the Huks (short version of Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon), a communist-socialist guerilla movement against the Japanese, ambushed a Japanese convoy and quickly disappeared.

In retaliation, the Japanese ordered everybody out of their homes to impose “zona.” At the City Hall, they separated the able-bodied men from the women and children. Manny was grouped with his older brother and cousin.

“It was raining and right behind us was a Type-99 machine gun. I still had not taken the whole situation seriously. To me, it was strange to see a machine gun with a banana-shape magazine atop the trigger assembly (like the British Bren gun, but which was mostly seen in Europe and the British colonies).

“But it became deadly serious when the Japanese forced the townspeople to identify escaped combatants from Bataan. Because we were near Bataan and Corregidor. Some of the townspeople fingered anyone to the Japanese in a desperate attempt to save themselves. The Japanese eventually released the women and children to go back home. But my father and the rest of the men who looked strong enough to fight, remained.”

The next day, Manny’s mom packed a lunch bag for him to take to his dad at the school yard. “I stopped in front of the schoolhouse and saw the sentry, eyeing the fixed bayonet on his slung rifle. And I made a quick u-turn back home.”

The Japanese banzai charge with fixed bayonets is stock image from World War II movies. In fact, Japan was the only nation in World War II to fix bayonets even on light machine guns. There’s nothing like the fear factor in seeing a Japanese soldier charging with the wicked bayonet and a blood-curdling cry. But experts say it was probably not in their infantry field manual. Japanese troops in the field found that attaching their bayonets to their rifle was better than wearing the long blade at their sides. Some officers had samurai swords.

“My older brother ended up bringing dad’s lunch,” Manny recalled. The family eventually left the old house. But wherever they went, they had to bow to a Japanese sentry or soldier.

“Even today, there are people in the countryside who harbor extreme prejudice against the Japanese. But I was not traumatized like that. I didn’t join the US Navy because of what happened in World War II. I originally wanted to join the Philippine Army, but my dad said, ‘You’re crazy. Wait until there’s an opening in the US Navy.’ Which I did after high school. I passed the physicals and exams. Six months later I was in San Diego.”

“When I was posted around the world, I had this notion when I was very young that the Japanese were monsters. But where I was posted, I found them to be very polite.”

He talked about the time he spent at a US Navy repair facility in Sasebo, Japan in 1972 when martial law was declared in the Philippines.

“Japanese troops in the field found that attaching their bayonets to their rifle was better than wearing the long blade at their sides.”

Manny spent 22 years in the US Navy and he shipped out all over. First with the “’gator navy” at the amphibious base in Little Creek, Virginia with an auxiliary personnel attack (APC) carrier for transporting Marines from Charlotte, NC in the 1950s. He got his first shore leave after three years and was stationed near Goodyear, Arizona, “a graveyard for obsolete aircraft.”

From 1959 to 1961, he was with the advisory group to the Korean Navy in Seoul. At the beginning of the Cold War, he was patrolling the Mediterranean out of Malta. He was in Havana when Fidel Castro was still up in the Cuban hills. Then he got his first combat ship – an old World War II destroyer in Long Beach. Shortly, he was called to a Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh city) repair facility in the Vietnam War.

Manny retired in 1975. He cared for his ailing dad in Orange County. When Enrique retired from Federal Service, he cooked for PAL. Because of that, Enrique flew anywhere in the world. Enrique died in the late 1970s.

Manny was a loner after he left the Navy. He was still searching for himself when he joined the San Jose Cursillo Movement in the early 2000s. He later suspected he was suffering from effects of Agent Orange and was about to seek treatment.

Manny Fernandez (standing, extreme left) when he joined the Filipino San Jose Cursillo Movement in 2014 (Photo courtesy of Titus Raceles/Marlon De Leon)

The last time Manny chatted with this writer, he intimated that his dad, Enrique, was also some kind of sports reporter for a Honolulu newspaper after the war. He speculated that Enrique’s Federal employment was more than that of a 9 to 5 civil servant. After reading Enrique’s written testimony below, one might miss the twist in his narrative – was he or was he not a guerilla?

But that’s not all, folks!

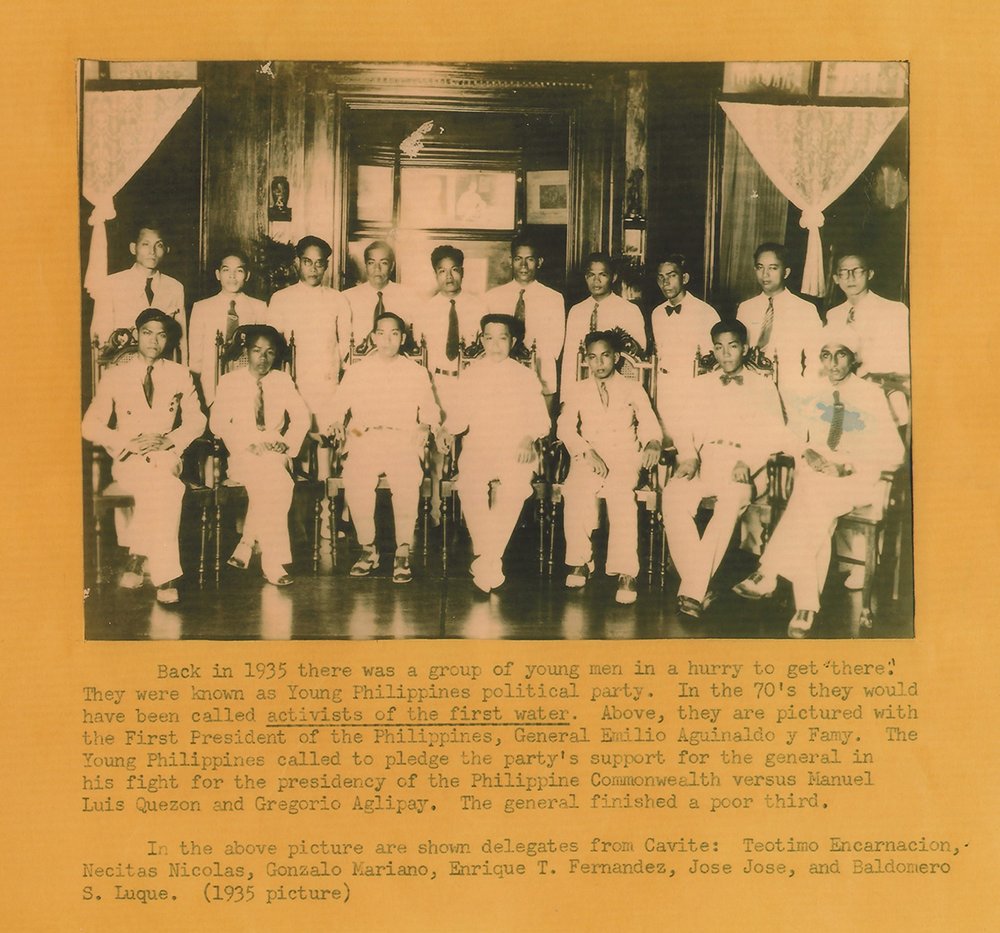

Manny gave this writer a photo from 1935 clearly showing Emilio Aguinaldo at the center, surrounded by members of the Young Philippines political party (of which Enrique was a delegate). This photo was taken at the time of Aguinaldo’s campaign for presidency vs. Manuel Luis Quezon and Gregorio Aglipay. Aguinaldo finished third.

Emilio Aguinaldo (seated, fourth from left) ran for president against Manuel Luis Quezon and Gregorio Aglipay in 1935 with his Young Philippines party including delegate Enrique T. Fernandez (standing, seventh from left). (Photo courtesy of Manny Fernandez)

But Manny’s last teaser was that he remembered asking his dad, Enrique, if Aguinaldo really had Bonifacio executed. Manny died before he could get back to this writer with the story.

Following is his dad’s testimony, verbatim, and this writer’s promise that it would see the light of day.

My Imprisonment in Fort Santiago

By Enrique T. Fernandez

Fort Santiago in World War II (Source: The Official Gazette)

I set forth herein my recollection of my imprisonment by the Japanese Army as a political prisoner from 18 August to 24 September 1944 in Fort Santiago, Manila – a harrowing 38-day experience. My objective in writing this memoir is to set forth in writing the information which my folks may have readily available should anyone enquire on the circumstances of my having been jailed.

In 1944 the Japanese occupation forces in the Philippines were jittery due to the relentless onslaught of American Forces led by General Douglas MacArthur. At that time the advance American units were already swarming over the Marianas Islands and the Trust Territories on their march to Japan and the Philippines. In fact, in October of that year the Americans landed in Leyte Island right in the middle of the Philippine archipelago.

Faced with this peril, the Japanese occupation forces exerted frantic efforts to instill fear and exact frightened obedience from the Filipinos. They resorted to conducting frequent “zona” of districts or specific areas which they suspected as harboring members of the underground. When an area was “zona-ed” all the men, and sometimes even women, who were caught in the dragnet were gathered and investigated.

Investigations were usually accompanied by physical injuries being inflicted on those investigated. The purpose of this “third degree” method was to extract confessions from suspects. Some of the brutalities included flogging, burning of the hair and skin, denial of food, forcing the victims to drink excessive amounts of water, making them kneel on ground sprinkled with finely ground stones, making them stare at the sun for a long period, and cutting or branding their skins with hot iron.

Because of these cruel practices the Japanese military was branded all over the world as the most sadistic.

On a purchasing mission to Manila

At the time of my capture I was managing a cooperative store in barrio Santa Maria, Licab, Nueva Ecija where I evacuated my family in early 1942. My wife’s family owned rice lands in this place and my wife had many relatives both on her father and mother’s sides.

As manager I was responsible for purchasing merchandise to be sold by the store. The store management decided to make purchases in August 1944 in Manila instead of at the usual source of supply – Cabanatuan. For this trip I was accompanied by Gregorio Augustin, barrio mayor and ipso facto president of the cooperative store; Basilio Victorio, store treasurer; and a member who joined us only for the purpose of traveling in our company; he left our group as soon as we reached Manila.

After many delays caused by strong rains and floods, our group finally left Licab on foot and by banca for Victoria, Tarlac province, on 15 August 1944. From Victoria we rode on a carretela to Tarlac, the provincial capital, where we spent the night. We rode the train to Manila the following day and took rooms in a hotel on Rizal Avenue close to the Cine Ideal.

During this period Manila was swarming with evacuees from the provinces, Japanese soldiers and their uniformed constabulary, and the spies for the Japanese and the Americans. The “buy and sell” business was brisk. Because the Japanese wartime currency was by then practically worthless – but it was the only legal tender at that time – people had to carry their money in paper bags or bayong (woven palm-leaf bags). A ganta of rice at the time in Manila cost something like one thousand pesos. Inflation was fast reaching its worst.

We went shopping as soon as we were settled in the hotel. We purchased hooks and fishing lines, sewing thread, needles, clothing material, dried fish, coffee beans, tobacco products, medicines for ordinary colds, and other goods generally in demand in the rural areas. We deposited our purchases with the hotel management.

That night we went around and observed the street crowds and the behavior of the café society. A general tension was noticeable everywhere. This was written on the faces of the people. However, few uniformed soldiers were seen in the streets, restaurants, movie houses, or entertainment places.

Trip to Cavite City

Early on the second day of our stay in Manila I went alone to Cavite City to see our household effects, which we left in our former house in the care of the new owner, our kumadre Josefa Calderon. I found our property in good shape. I packed several books and some clothes that I wanted to bring to Manila and eventually to my family in Licab.

On the bus from Manila to Cavite I met several acquaintances including one Japanese who grew up as a boy near the pool hall I frequented often and for many years until the Second World War broke out. He was known to us only as Pong. He was the son of Saki, who owned a general store near the public market. Since Pong and I were friends we conversed rather frankly and intimately. We talked of the war, life in the provinces, the underground, the local government, etc. Subsequent events proved that I should not have talked on these subjects at all. Japanese spies were active in every conceivable place at the time.

Before returning to Manila I called on two Japanese acquaintances who were working in the Japanese garrison in Cavite City. These were Sunkichi Arikawa, who owned the restaurant and hotel near the Dreamland Cabaret and where I worked as night manager for a while, and Saki, who owned and managed a general store near the public market. Saki and I used to play pool or billiards almost nightly before WWII.

Arikawa informed me that Saki was called to active duty in the Japanese Army. He held a reserve commission as Colonel of the army. Arikawa worked as a civilian and was charged with purchasing local foodstuff for the garrison. He was very surprised but glad to see me. We talked about old times for a while but eventually our conversation turned to the war. He knew I worked for the American Navy Yard in Cavite. When I broached to him my desire to engage in the business of supplying fresh farm products to the Japanese occupation forces, he advised against the idea and instead told me to return to my family in the province and stick to farming. We parted as friends although our sympathies were on opposite sides of the raging war.

I returned to Manila late in the afternoon and joined Kumpadre Guying (Gregorio Agustin) and Ka Basilio (Basilio Victorio) at the hotel at about 8 p.m. Before we went to sleep we readied all our cargo and personal effects for loading in an early bus bound for Cabanatuan on the morrow.

Caught in a ‘zona’ dragnet

That night there were several husky men who occupied rooms near the stairway. They appeared friendly and were cordial to us even if we had never met them before. We thought then that they were guerillas. They even unfolded a map showing the location of American forces. Their information jibed with what we knew from the newspapers which, of course, were controlled by the military. Thinking now over the events which followed, I believe that these men were Japanese spies who were planted to coordinate the “zona” described below.

That evening in the hotel was similar to other evenings before. There were muffled conversations behind closed doors. Women of the night came and went, plying their age-old trade. There were drinking bouts in some of the rooms. Gambling was in progress in a corner room. By midnight nearly everyone was asleep. Our group, all berthed in one room, went to bed early since we planned to check out in the wee hours of morning and proceed to the bus terminal in hopes of getting space on the first Cabanatuan-bound bus.

At around 2 a.m. the hotel residents were rudely awakened by the wailing of sirens and the banging of doors. Soldiers were running from room to room ordering all to assemble immediately in the basement. All were ordered to dress up quickly and join the lines.

We reached the basement in about 5 minutes. We noticed that the husky men and the prostitutes were not in the lines. We were loaded in trucks and rushed to Fort Santiago. There we were assembled in one big hall. Both sides of Rizal Avenue from Carriedo Street to Azcarraga Street (now Recto Avenue) were “zona-ed.” Some 2,000 men and some women were hauled to Fort Santiago that night.

“It suddenly dawned upon me that the Huks and the guerillas were at loggerheads although both were then pro-American and anti-Japanese.”

Arrested and confined

We were formed in a single line and marched to a wall were spies and witnesses looked us over through peep holes. These hidden accusers signaled who among us were to be retained. Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio were lined up immediately behind me. I was ordered to join one line while both of them were ordered to join another. The persons in our line numbering some 400 were retained, finger-printed and assigned to cells. I found out later that the persons in the other line were given a lecture on obedience and cooperation with the Japanese occupation forces and then told to return to their homes.

During the processing I was shown the boxes of merchandise we purchased for the store, my books and personal clothing, and the money which I had in my wallet and in the pockets of my extra pair of pants. I claimed the entire lot as mine and this information was noted down on my processing card.

I subsequently found out that my companions, Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio, left for Licab after waiting one day for my release. They brought home and gave to my wife my toothbrush, pipe, pipe tobacco and towel; they lied to my wife saying that I had decided to stay a few days longer in Cavite City and that I would return to Licab probably in a week or two.

Prison conditions

I was marched along with others to Cell No. 4. This was located on the ground floor of a newly constructed building adjacent to the old fort. This cell measured some 8 feet wide and some 24 feet long. At the rear was a toilet and faucet from where we drew our drinking water. We were 25 in the room. It was so crowded that when we slept at night we had to lie down on our sides and arrange ourselves head-to-toe. Ventilation was provided by the natural flow of air through small openings in the front and in the back of the room.

Prison routine

During the day we were ordered to squat and since it was warm we generally took off all clothing except the underwear. Absolute silence was required of us, any conversation made was by whispers and only when the cell guard was not peeping in. We kept our personal clothing and used them as pillow or blanket.

Meals were served at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Meals consisted of soft rice (lugaw) and boiled vegetables (usually kangkong) and a small portion of fish or meat. This definitely was starvation ration. There were days when we were served only one meal.

At 6 a.m. and again at one and 10 a.m. the guard ordered a count of the prisoners. During this ceremony we were required to stand, stretch, and each shouted his number in Japanese in numerical sequence, which is itchi, nee, san, chi, go, roko, etc. If the count did not tally with the posted number of prisoners in the cell the guard ordered a recount. The purpose of this exercise was to ascertain if any prisoner had escaped.

No sooner had I settled in the cell, stripped down to my underwear, and not moving, then the bedbugs and other blood-sucking insects began to work on me. At first the scratchiness was almost pleasant and tolerable but after several days I had sores on my behind and even on my legs and arms.

Twice a week we were marched out of the cell and taken to the showers which were located in the open area between barracks. We relished these occasions very much as the water and soap somehow impeded the spread of skin diseases, and the fresh air and sunshine invigorated our bodies.

Investigations

My investigation started timely enough on the second day of my confinement. I was called out by the cell guard at around 3 p.m. and turned over to an investigator dressed in civilian attire, who took me to a large room atop the fort. He accused me of being a guerilla, a member of the underground. I denied the charge. He belabored the subject and I, on my part, steadfastly denied my being a guerilla.

My position was that I had no inducements for joining the underground because I had a wife and five small children to support; that my wife had rice lands which yielded sufficient food to satisfy the needs of our family; and that I had an important job of managing a cooperative store which served the people of our barrio.

I was returned to our cell after one hour of questioning. No physical force was applied to me during this interview.

The second interview was held two days after the first. The investigator was other than the first, also dressed in civilian clothes. He repeated the accusation that I was a guerilla. I again denied the charge. He repeated the same charge in different words, striking my waist, legs, shin and shoulder with a piece of wood as he repeated his accusation. I stuck to my denial although I was suffering pain from the flogging.

He accused me of having worked for the Americans. I did not deny this charge. I told him that I worked for the American Navy yard in Cavite, and I did it because the Americans paid me more than the Mitsui Bussan Kaisha, the largest Japanese firm in Manila, was willing to pay me. I worked for the bigger salary not because I loved the Americans or that I hated the Japanese. I told him my decision was based purely on economics.

The other prisoners were also called out for questioning. Those with serious charges such as sabotage, murder, attack on Japanese installations or personnel, were called to the investigation rooms at eerie hours of the night between midnight and 4 a.m. Some came back bleeding and badly bruised. Some of them were subjected to flogging, hanging, and water treatment. Others whose bodies were badly burned or who suffered serious injuries were not returned to their cells. They were either sent to the hospital, sentenced and executed, or sent to the national penitentiary to serve their sentences.

Hanging

I was called to the investigation room 5 or 6 times. Except for the first, each interview was accompanied by flogging and slaps on the face. However, the last one was the most difficult. The investigator repeated the same charge and I repeated the same denial. He hanged me: he pulled my hands behind my back, tied the thumbs together, put the rope through a pulley up in the ceiling, stood me on a chair, kicked the chair from under my feet, and I was dangling up in the air still shouting my denial of being a guerilla. I passed out and when I regained consciousness I was sprawled on the floor wet with water which was (splashed on) my face in order to revive me.

Confrontation

The next interview was more ominous than the others. I was told to put my shirt on. I was taken to an office where an officer in uniform sat at a table. Beside him was a Japanese civilian interpreter, and next to the interpreter was a husky man I had not seen before. The face of the Japanese civilian looked familiar to me, but I could not recall where I met him. I was stood in front of the officer and asked questions regarding the location of the guerilla unit to which I belonged, and the names of the other officers. I told the interpreter that I was not a guerilla, and I did not belong to any guerilla unit. The officer looked at the other man in the room and although he did not speak, his gesture seemed to say “Now, what do you say?” The man spoke to me and informed me in Cebuano Visayan that he and I were companions in the operations in Cebu and Tondo. I again denied this charge. The officer left the room at this juncture.

Soon thereafter the interpreter asked the man in Tagalog if he was telling the truth. The man could not answer. The interpreter slapped him vigorously and several times on the face.

The interpreter returned me to our cell. On the way he told me that he studied in the Jose Rizal College in Manila and that he thought he saw me there. I told him that I took courses in that college in 1929, 1930, 1939, 1940 and 1941. He said he was there in 1940. This fact may have had a bearing in the decision on my case.

Release

I was called out again some 10 days after the confrontation with the false witness who, I found out later, was the wartime police chief of Pasay City. When I was called out I was ordered to bring along all my clothing and other belongings. Upon hearing this my cellmates concluded that either I was to be sentenced and transferred to Muntinlupa, or be executed, or be released. They told me, whatever the decision may be, I would have no further need for my other clothes. They begged me to give them my undershirt, small towel, handkerchief, and extra briefs. I gave these items to the ones closest to me in the cell.

I was conducted to the main hall where already there were three women and two men lined up before a uniformed Japanese officer. I was placed beside the men. The officer told us that the charges against us were not substantiated, that he and the Japanese Army were sorry that we were inconvenienced, and he appealed to us to lend our full cooperation with the occupation forces and the government.

My personal belongings and money were returned to me intact. We were released and I got out of Fort Santiago late in the afternoon of 24 September 1944.

A humorous twist

There was one humorous twist to my investigation. Almost every time I was asked if I were a good citizen and supported the government, I would show my residence certificate at the back of which was a typewritten notation stating that I was a law-abiding citizen and a good supporter of the government. It was signed by the Provincial Governor of Nueva Ecija. I did not know then that while I was exhibiting the certificate in my defense the Provincial Governor of Nueva Ecija was himself confined in the cell adjoining ours. He had been arrested and accused of being a guerilla. Had the Japanese known of this fact they might have prolonged my imprisonment.

While I was confined in Fort Santiago our unit of the PQOG (President Quezon’s Own Guerilla) under Colonel Eligio Ramos, native of Urbiztondo, Pangasinan, was conducting operations in Eastern Pangasinan and La Union.

Cellmates

Some of the more prominent men confined with me in Cell No. 4 were General Vicente Lim, first Filipino to graduate from the West Point Military Academy; Jesus Marcos Roces, who was elected Vice mayor of Manila soon after the war; and Mr. Consing, son of the Governor of Iloilo. Other acquaintances who were also in the Fort during my confinement were Atty. Bautista, president of the Civil Liberties Union; and Colonel Emilio Baja, of Noveleta, Cavite, who wrote the history of the Philippine flag.

There were many others confined in the Fort as at this time; anyone who was suspected of membership in the underground was arrested and locked up in Fort Santiago or in any of the many confinement centers in the city and in the provinces.

‘I was hospitalized for a long time’

From Fort Santiago I hired a tricycle to the bus terminal near the Far Eastern University, hoping to get a ride to Cabanatuan that evening. Being informed that there were no night trips, I proceeded to the house of my aunt Oping (Merope Ramos-Damian) on the corner of San Marcelino and Singalong. I arrived there at about 7 p.m. The neighbors were suspiciously staring at me as I called to my aunt. I was a strange sight to them: emaciated, bearded, with long unkempt hair, sickly pale, and lugging several boxes of merchandise. Aunt Oping assured them that I was her nephew and that I just got out of the hospital after an extended illness.

She even accompanied me to the barbershop when I went for a shave and haircut. She had to explain to him and to the onlookers about my having been hospitalized for a long time, hence my unsightly appearance.

My aunt had to lie about my imprisonment as in her neighborhood were living many spies of both sides and if it were known that I have been suspected of being a guerilla the pro-Japanese undercover man would surely take me.

Homeward bound

Early the next morning I went to Cabanatuan by bus. The trip was nerve-wracking as the roads were bad and there were Japanese roadblocks along the way. We arrived in Cabanatuan late in the afternoon. There were no more buses going to Licab. I lodged in a hotel near the Japanese garrison. I was assigned to a big room, alone. Late that evening a man carrying a sack of rice, came to the room and occupied a corner opposite my bed.

At about 2 a.m. the Japanese military police came to our room and inspected our baggage. The sack of rice yielded a 45 cal. pistol and some ammunition. The man and his rice and his gun were taken away. I was not able to sleep during the rest of the night.

At sunrise I left the hotel and went to the public market where I got a ride on a carretela bound for Quezon town, adjacent to Licab. In the same vehicle, luckily for me, was Ating Orang Lina, my wife’s cousin. She was surprised to see me alive. She already heard of my disappearance more than a month ago and like the others had given me up for dead. The trip of some 35 kilometers over rough roads took a long time. We arrived in Quezon town around 4 p.m.

Ating Orang and another relative accompanied me to Santa Maria. They carried on their heads the several pieces of cargo I had with me. We took a short cut to Santa Maria over rice fields. At the entrance to Santa Maria we were stopped by a Huk soldier. There was at the time one squadron of Huks deployed in our barrio. The soldier suspected me as a Japanese spy. I was allowed to enter the barrio only after the barrio people recognized me and vouched for me.

‘Was I liquidated, murdered?’

My wife and members of her family were shocked when Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio returned without me. They were, however, somewhat calmed by the explanation that I stayed behind with our folks and friend in Cavite City and that I would return to Licab in a week or two.

When I did not show up after two weeks my family became alarmed. They imagined all sorts of harm that could had befallen me. Could it be that Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio had me liquidated? Murdered? For professional jealousy, perhaps?

During that critical period of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines there were many unexplained murders. Men disappeared and were never heard from again, or if their dead bodies were found no one ever found out who killed them.

My wife, my mother-in-law, my wife’s older sister, Atang, alternated in going to the cooperative store daily, and sometimes more often, and accused Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio of having murdered me or having arranged for my murder. They based their belief that I was already dead on the fact that if I were alive, as both of them claimed, they could not have returned with my toothbrush, pipe, pipe tobacco, and towel. These were inseparable to me, my wife claimed.

Poor Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio: They could not tell the truth that I was confined in Fort Santiago. My wife had at that time delivered our daughter Evangelina less than a month before and was therefore weak and pale. The shock might kill her.

Reunited at last

When I was being questioned by the Huks at the perimeter of the barrio some children saw me; they ran to our house and informed my wife. When we finally arrived the whole family was already assembled in our house.

My reunion with my wife and children was emotional but very happy. Everyone inquired all at once where I had been, why, how, etc. I told them that I was confined in Fort Santiago suspected of being a guerilla. There I stopped. It suddenly dawned upon me that the Huks and the guerillas were at loggerheads although both were then pro-American and anti-Japanese. They sometimes fought pitched battles in our area. I think that these battles were to determine which of them was to lord over our barrio.

The barrio learned quickly of my arrival and most of the people rushed to our house. Our house was so packed with people that supplemental posts had to be erected on the spot for fear that the floor would collapse. Many spoke few words but their eyes revealed how much they marveled at the unseen Hand that controlled the destinies of men.

My arrival eventually cleared up everything. Kumpadre Guying and Ka Basilio and my family became good friends again. Barrio life – slow, deliberate and neighborly – soon healed animosities and hatreds which my disappearance migh have engendered.

With the loving care of my wife and in-laws and friends I soon regained the 30 pounds I lost during my confinement. I even got rid of the sores with the use of medicines from herbs and tree leaves.

Not easily forgotten

Nearly 29 years have elapsed since my confinement in Fort Santiago. The memory of those events, however, has remained deeply engraved in my mind so that even at this late date I am able to write this memoir in this form.

(Signed Enrique Fernandez)

Honolulu, Hawaii

March 19, 1973

Harvey Barkin edits The Filipino American Post in San Francisco and reports for BenitoLink in San Benito County. Previously, he was editor for FilAm Star, freelance reporter for San Jose Mercury News and reporting fellow for campaigns and grant-funded projects. He was also a tech writer for Silicon Valley start-ups and a book reviewer for Independent Publisher, then Small Press.

More articles from Harvey I. Barkin

No comments